The name of Honeysuckle Creek and the excellence implied by that name will always be remembered and recorded in the annals of manned space travel.

Christopher C. Kraft, Jnr, Director, NASA JSC, Houston, Texas

Meet Scarlet O’Barbara my research-mobile, the old Toyota Camray wagon gifted to me by a literary friend in Canberra for our Big Skies Collaboration. Scarlet’s job, for the next few years, is to haul me and my kit the full length and breadth of Australia’s 700 Kilometre Array (700KA) of astronomical observatories to research my new book, Skycountry, and to implement the Skywriters Project (if/when it’s funded). Scarlet is more than a mobile field station and occasional bunk though. She also serves as a literary trope, a blazing red synecdoche, or material metaphor if you like, for all the things we Earthlings are doing to disrupt or extinguish our home planet’s life-support systems. We’ll return to this theme later, but first to Honeysuckle Creek.

So there we were, Scarlet and me, cruising up Apollo Road, in the Australian Capital Territory’s Namadgi National Park, looking for the tracking station from which those first fuzzy black and white television images of the Apollo 11 moon landing were relayed to NASA’s Mission Control Center way back on 20/21 July, 1969. Remember that “giant leap for mankind” towards colonising our moon and other moons, other planets, other galaxies? Were you old enough, like me, to have watched Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin walking on the moon that day?

Honeysuckle was one of three installations to receive the moon images. The other two – CSIRO’s Parkes Observatory and NASA’s Goldstone Deep Space Communications Complex in California’s Mojave desert – are still listening to the Cosmos, but not Honeysuckle Creek. It was dismantled in 1981 after some 15 years of active service supporting NASA’s space missions. The staff were dispersed, their offices, labs and workshops demolished, their landscaped gardens too, and even the antenna which received those historic images is gone. Today all that remains are the tracking station’s concrete slabs, a few stubs of pillars and posts, some protruding bibs and bolts, and a stairway to nowhere. That thrill of engineering excellence, technological innovation and scientific achievement which once radiated from this site have been replaced by the hum of bees in the encroaching wattle trees, the twitter of small birds, and the occasional tread of bushwalkers’ boots, or of curious day trippers like me.

For me, Honeysuckle Creek in 2016 was a surreal and haunting place, even post-apocalyptic. Those concrete slabs and stubs evoked all the Cold War fears I had grown up with: remember that superpower strategy of Mutually Assured Destruction and its consequence, Nuclear Winter? If those Cold War warriors had unleashed their worst back then whole cities would have looked like Honeysuckle Creek today.

The Cold War between the planet’s two superpowers of that era, the United States and the Soviet Union (USSR), with Australia as a compliant US ally, is part of the broader historical context of the Honeysuckle Creek Tracking Station. The missions it and other NASA tracking stations supported in the 1960s and ’70s were part of what is now remembered as the Space Race, which paralleled the superpowers’ Nuclear Arms Race and their ideologically driven conventional proxy wars in Vietnam, Afghanistan and elsewhere. By 1981, when Honeysuckle was dismantled, the Cold War was thawing and, indeed, by 1991, the USSR had ceased to exist. Many individuals and organisations, including people associated with NASA, had cooperated across these ideological boundaries during the Cold War years, of course, but the ghosts of that era remain.

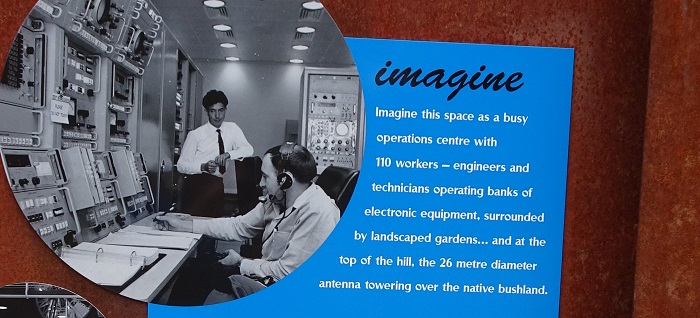

The old Honeysuckle Creek Tracking Station site is nevertheless of great cultural heritage significance to Australia and the world, as the array of weathered steel interpretation panels on the concrete slabs acknowledges. The signage memorializes the station’s staff and the contributions they made to NASA’s space missions, including the Apollo program and its moon walk in particular. As one of the panels reminds us,

The staff at Honeysuckle were privileged to participate in the 20th Century’s greatest adventure into space. The buildings and equipment with which they worked have long been removed, but this site and their memories will remain a part of mankind’s history on this planet.

And who could argue with that?

Since its physical demise, Honeysuckle has also acquired a strong online presence. It now has its own tribute website, for example, and lives again in the many books about the Apollo and other NASA space programs. One of the old “trackies”, Hamish Lindsay, has written Tracking Apollo to the Moon, for example. I’ve ordered a copy and am looking forward to reading it. I’m also looking forward to meeting some of the people who worked at Honeysuckle after the first concrete slabs were poured. I warmly invite any of you who are reading this to add a comment to this post, or to communicate with me by clicking <Contact> on the top menu. I’d love to hear from you, or anyone else who recalls this or any of NASA’s other 20th century tracking stations; and to even perhaps interview you for my own book.

As I wandered through the native bushland surrounding the remains of the tracking station, and inhaled its Spring fragrance, I couldn’t help but wonder about what this site had meant to the First Peoples of these mountains and valleys. They had been observing celestial objects for millennia before Honeysuckle Creek and its 700KA near-neighbours in the ACT, Orroral Valley Tracking Station, the Canberra Deep Space Communication Complex at Tidbinbilla, and the Australian National University’s Mt Stromlo Observatory were built. What did the mountain ridges, valleys, and big granite tors surrounding the site mean to these first sky watchers? How did they understand the moon, the stars and planets, and the dark spaces in between? What knowledge, what survival strategies, what beliefs were embodied in these celestial objects for them? What sky stories did these First Peoples tell?

We know that people have been watching the sky from these ridges and valleys for at least 25,000 years, and probably much longer, as archaeological remains from a rock shelter in nearby Tidbinbilla Nature Reserve tell us. The presence of these First Peoples is also revealed by ancient hearth sites, rock art, scatters of stone tools and other assemblages, ceremonial pathways and trading routes, ethnographic works authored by 19th century Euro-settlers, and by stories which have survived the impacts of colonisation to be now shared by Ngunawal and/or Ngambri descendants. We therefore know, for example, that the Ancients harvested bogong moths [more] from rock fissures and crevices in the mountains each summer, and gathered together at this time of year to feast on barbecued moth bodies and protein-rich moth cakes. They socialized at this time, traded, arranged marriages, negotiated alliances and conducted other intertribal business, initiated young people, exchanged knowledge, participated in religious ceremonies, and shared stories, both old and new, as poetry, dance and song.

Astronomers may also have had an important role in these gatherings, since their observations of the movement of the sun, moon, stars and/or planets in relation to particular landscape features may have determined the timing of events; and almost certainly clansfolk used celestial navigation to find their way to the gathering sites. Our Big Skies Collaboration cultural astronomer Trevor Leaman and his colleagues will know more about all this. I’ll ask them. And are there any Ngunawal or Ngambri descendants, or descendants of other First Peoples, who would like to tell us what your skyscapes and landscapes mean to you?

NASA’s Honeysuckle Creek Tracking Station existed for less than two decades, just a flicker in time compared with the more than 60,000 years people have been gazing at the Southern Sky from Australia. Most of the raw data sets collected by tracking station staff in the 1960s and ’70s have, I expect, survived (notwithstanding recent controversies about the Apollo 11 tapes), and have been processed, analysed, tested, utilised, theorised, revised, and augmented many times to become reliable information and knowledge, and perhaps even wisdom. This intellectual legacy is preserved now in digital data banks, books, scientific journals, web sites and myriad other knowledge storage systems as part of humanity’s shared cultural heritage.

For the First Peoples, however, there was only one knowledge storage device: the human brain. All the data, information, knowledge and wisdom they accumulated over tens of thousands of years, which was so fundamental to their survival as individuals and as a people, was stored in human memories, and required regular iteration to be retained and passed on to others. Elders devised sophisticated mnemonic strategies to ensure the generational and intergenerational integrity of their knowledge base. They encoded their knowledge in stories, rituals and songs, some so secret and sacred that only the most respected people had access to them; and they linked these narratives with specific land and sky features to create what Lynne Kelly calls “memory spaces“. These memory spaces were organised into songlines which enabled people to retrieve the embedded knowledge as they walked their Country, and simultaneously reinforce their own memories by singing the stories and performing the appropriate rituals.

Such memory-based knowledge systems ensured the survival of cultures for tens of thousands of years, but they were always extremely vulnerable to disruption and worse. If the rememberers die prematurely or were incapacitated or weakened by the processes of invasion and colonisation; if memory spaces were destroyed; if access to them was denied; if life support systems were debased or destroyed; if people’s lives were made immeasurably miserable … then the transmission of critical knowledge from one generation to the next was degraded or ceased completely. As a consequence, millennia of learning was lost forever. The psychological, social and cultural impacts of this loss lasts for generations. In Australia, as elsewhere, descendants are still suffering the trauma of these impacts.

Even in highly literate cultures critical knowledge can be lost forever, as we have seen many times in the past. Now, however, our greatest threat is not the loss of collective knowledge but our collective failure to act on what we already know.

Which is where Scarlet O’Barbara, my petrol guzzling research mobile, re-enters this story. There she is below nosing her way into another photo of Honeysuckle Creek: a blazing red metaphor for all the things we Earthlings are doing to threaten our own survival, and the survival of the other species we share our home planet with. Scarlet pricks my conscience every time I get into her driver’s seat.

When I began this post I was quietly despairing about humanity’s failure to act decisively on our accumulated knowledge about the global consequences of burning fossil fuels in spite of all the warnings and the activism of so many good people. At the time, leaders of Earth’s nation-states were lining up behind the two biggest carbon polluters, the US and China, to ratify the Paris Agreement on Climate Change to keep the rise in global temperature below 2 °C above pre-industrial levels. Scientists had already warned us, however, that Paris was too little too late, and that very dangerous times lay ahead. Yet here in the Australian Capital Territory, their warnings caused hardly a ripple in the corridors of power. Indeed, some of our elected parliamentary representatives even denied that Climate Change was real!

As Australian science writer Julian Cribb persistently reminds us in his articles, and in his new book, Surviving the 21st Century (Springer 2017), we have more than rising CO2 global temperatures to worry about though. Cribb lists 10 interconnected human-induced existential threats to humanity’s future on Planet Earth: global warming, ecological collapse, resource depletion, weapons of mass destruction, global poisoning, food insecurity, population and urban expansion, pandemic disease, dangerous new technologies and … self-delusion. Such threats are all possible consequences of our political and industrial leaders’ failure to heed that data, information, knowledge, wisdom – call it what you will – that some of our planet’s smartest and most authoritative people have produced over the past 50 years. Some of these experts, like cosmologist and theoretical physicist Martin Rees, fear that we might not even make it to the end of the 21st century. (Rees gives us a 50-50 chance! Others would give us less!) So might the concrete slabs of Honeysuckle Creek be our future as well as the old tracking station’s past?

I weep on you, Scarlet, as you spew your CO2 into the atmosphere.

Back in 1969, those fuzzy black and white images of the Apollo 11 moon walk, as relayed from Honeysuckle Creek, Tidbinbilla and the Parkes Observatory, really excited me; and I’m still excited about humans leaving Earth to explore and possibly colonise other moons, other planets, other galaxies. But–and call me a Romantic if you want–I don’t want us to HAVE to leave because we’ve stuffed up here at home. Do you?

And if and when we do colonise other planets and/or moons, I don’t want us to do it the way Europeans colonised Australia and so many other parts of the world either. Because we now know what happens when ….

I’m getting morbid . Time to wrap this thing up. I’ll leave you with another Apollo image: Earth rising over a barren moonscape, as photographed by the crew of Apollo 8 seven months before that “giant leap for mankind”. The little blue planet we call home.

Dr Merrill Findlay

Big Skies Collaboration

October 2016

Page published 10 October 2016. Last updated, with a few minor copy edits, on 1 November 2016, again on 9 Nov. to add a link to an interesting Canberra Times article on Bogong moths, and again on 14 December with some minor edits. And I found more typos to correct on 8 January 2017.

Permalink: https://bigskiescollaboration.wordpress.com/2016/10/10/honeysuckle-creek/